No prescription seems to arrest the decline of Europe. No single prescription, at least.

A capsule for solidarity, a tablet for a banking union, syrup for a deeper political and monetary union and an injection for sustainable and inclusive growth, sit neatly in the pillbox and the finest of practitioners have failed to prescribe the right mix of pills to cure the deeply infected Europe.

On 25th February 2013, The Centre for Global Economic Governance, (CGEG) at Columbia University, New York invited the practitioners themselves to prod on the diagnosis and detail best practices in a discussion on the Future of Europe. Ambassador Anne Anderson, Permanent Representative of Ireland to the United Nations; Kemal Dervis, Vice President and Director, Global Economy and Development, The Brookings Institution; George A. Papandreou, Member of Parliament and Former Prime Minister of Greece; George Soros, Chair, Soros Fund Management LLC; Nobel Laureate, Joseph Stiglitz and Jan Svejnar, Director, CGEG, sat on the same side of the stage to share their opposing views.

Lee C. Bollinger, President of Columbia University set the stage for discussion and in his opening remarks said, “I think all of us really want to hear how Europe is going to evolve, I would just say that someday I would like to have a job where all you do is say, ‘we will do whatever it takes’ and then the whole world relaxes and everything goes on from there”.

Svejnar invited Anderson to open the discussion with her thoughts.

“I am a committed European, intellectually and emotionally”, Anderson said. “At the same time I do not consider myself any kind of cheerleader for the European project”.

She added, “I want to make two points in my short ten minutes here today, and the first is that I genuinely believe that Europe will regain the momentum despite the current political difficulties, and secondly, I think my own country, Ireland, is going to contribute to it”.

According to Anderson the political and the economic are inextricably interwoven.“At each stage where there has been a significant leap forward in Europe, you find that same interweaving of the political and the economic. And indeed the dream of the euro, when Kohl and Mitterrand had it, it was essentially a political response to the changed map of Europe”, she said.

While it is true of the past, the past is hardly the prologue to the future. It is not just a euro crisis that engulfs Europe rather an existential crisis. Anderson believes that despite the difficulties there will always be a political imperative that will continue to drive us forward.

“You have got to look at the bigger story that is out there today, it is the changing, evolving nature of global power, the redistribution of power. Despite the setbacks and difficulties that they are encountering, the reality is that Asia, Latin America, Africa are on the rise, and for Europe it is a question of innovating, integrating or declining”.

For Anderson the first step would be to retool institutionally. ‘We started doing that with the Lisbon Treaty and that will have to be further worked through. We have other big issues, for example, we talk so much, and it is true, about the need to connect with our citizens, democratic legitimacy, and democratic accountability: very, very real issues’, she said.

Anderson recognized the euro problem as urgent. She accepted that in the past, there had been mis-steps and mis-diagnosis but also believed that despite the wrong decisions, the European Central Bank was now stepping up to the plate. Taking the example of the European Stability mechanism, she pointed towards a banking union and referred to it as the biggest financial firewall in the world.

Explaining the situation in Ireland, Anderson said, “I think you all know the arc and the narrative for Ireland: the years of, the great years of the Celtic Tiger, the phenomenal growth, the property bubble, the banking crisis that became a sovereign debt crisis, the bail out, the austerity and now, thankfully the glimmer of recovery. And I do not want for a moment to underestimate the difficulty and the hurt in Ireland: It is very, very real. But at the same time, the trend is positive. We have got our competitiveness back in a really significant way, the competitive costs are down, our exports are doing very well, foreign investment is doing exceptionally well, we are back in growth – it is very, very modest but it is real, it is growth”.

Going forward, Anderson suggested two ways – One, accepting national responsibility through all the austerity measures and the second being European solidarity.

“After all solidarity is what Europe is about, but there is an even more particular onus for solidarity in this case, because if the Irish banks borrowed heedlessly and fecklessly perhaps as some of them did, then there were banks who loaned to them who were equally heedless in their loaning, and the fact that the Irish government behaved so responsibly in its response to taking on the bank debt on the shoulders of the Irish taxpayer. Had we not behaved so responsibly the repercussions would have been enormous all over Europe”, Anderson said.

The way forward in Anderson’s view is an accommodation between taking national responsibility, facing up to it and at the same time assertively making the claim for European solidarity.

Disagreeing with Anderson’s optimism, Philosopher and Economist, George Soros stepped in and said, “I happen to disagree with your optimism. I am afraid that the European Union is in an existential crisis. The problems of the euro have already transformed the European Union from what it was originally conceived, into something radically different because it was meant to be a voluntary association of equals and today it is difficult to escape from obligation where the debtor countries are subordinated to the dictates of the creditor countries and have effectively been relegated to second class membership. And I think this is politically not acceptable”.

Soros breaks down the financial problems into a sovereign debt problem, a banking problem, a balance of payments problem and a competitiveness problem. He points out to the complexity of the course of events that have been largely influenced by misconceptions, misunderstandings and the sheer lack of understanding of this complexity.

Soros believes the Maastricht treaty was a flawed design as it created a currency union without a political union.

He added, “The euro had several other deficiencies of which the architects were not aware. For instance, it assumed that imbalances would only come from the public sector because the markets were supposed to correct their own excesses. But actually the euro problem really came from the private sector, the banking sector. But that is not the most serious. The most serious deficiency is that the member countries by transferring their seignorage rights to the European Central Bank were actually indebted in a foreign currency, which they did not control and that raised the prospect of default, because normally a developed country would never default on its debt because it could print money. But the members could not do that and that is where I would say the central problem lies”.

Soros explained that at the time when the euro was introduced it was assumed that the government bonds were riskless and the banking authorities did not require commercial banks to hold any reserves against the risk. At the time, the European Central Bank accepted all the government bonds on equal terms at the discount window and this created a perverse incentive for the commercial banks to buy up the government bonds exactly of the weaker countries, which were at the beginning, selling and offering a higher yield because of the risk premium than the others. The banks thus got loaded up with the debt of the weaker countries.

“Even then the markets did not particularly react. It was only when Greece announced that the previous government had misstated the deficit, and it was much larger than it was expected, that’s when the markets suddenly woke up to the possibility that Greece may default. And then they raised the risk premium not only on Greek bonds but on all the weaker countries, with a vengeance”, Soros explained.

He continued, “And that created both a sovereign debt crisis and also a banking crisis because the banks were so heavily loaded with those debts. The result has been that we have gone from crisis to crisis and Germany did the minimum that was necessary to preserve the euro, but no more, and that is what maintained the crisis condition that is now four years old”.

According to Soros the underlying problems are of two kinds: One is a political problem that Germany is in the driver’s seat. While Germany does not dictate policy, no European policy can be proposed without first gaining the approval of Germany. The second impelling problem is the fact that Germany is imposing austerity on Europe, which is considered a wrong policy move by several economists. Soros explained that you have to shrink the deficit in order to shrink your debt. However, the debt is a ratio of the accumulated debt to the GDP, and if one reduces the budget, one also reduces the GDP. In the conditions that currently prevail, of insufficient demand, the so-called fiscal multiplier is more than one. In other words, if the budget deficit is reduced by one euro, the GDP falls by more than one euro.

Soros asserted, “I think the situation is going to continue to deteriorate and I think and expect perhaps after the German elections there will be a change in German attitudes. Europe is today an outlier in maintaining this orthodox financial policy. Major countries are engaged in quantitative easing: Japan is the latest convert. And quantitative easing is in a way another way of indirect currency devaluation. The decline in the yen and in the sterling is actually going to affect German exports. So by the time of the elections, I think Germany will also be in a recession”.

Dervis, Vice President at the Brookings Institution added his point of view and said, “Europe is a great political project, an incredibly successful political project, creating a zone of peace in a continent that not only tore itself apart, but the world with it. And I think there is tremendous and justified resistance against anything that deeply threatens that project”.

He added, “The essential problem itself has not been resolved. Unemployment in the Eurozone is now close to 12%; In Greece and Spain, it is over 25%. Youth unemployment in many countries is between 30 percent and 50 percent. The social suffering is terrible. And I think it is a kind of reflection on the world we live, in that, financial markets can celebrate while vulnerable people can suffer as much as they do in large parts of Europe today. So I do not believe at all that the problem is solved”.

Soros condemned that during an imbalance the whole burden falls on the deficit countries that maximizes the cost and it would be much easier if the surplus countries helped. He insisted that both the deficit country and the surplus country should help.

“The country in the world with the largest current account surplus is Germany. Moreover, if you aggregate northern Europe, both the Eurozone countries and the Scandinavian countries into one geographical group, the surplus of these northern European countries is bigger than US $500 billion. So this is one issue that will have to be addressed. As long as the northern Europeans do not pursue a more expansionary policy at home and do not reduce their own surplus, it is an imbalance, a very serious imbalance”, Soros said.

Soros argued for a political will to further integrate Europe. “You cannot have a common currency without much stronger integration of overall economic policy, fiscal policy, budgetary policy, banking regulation – the banking union has in principle been decided on – so there is this need, if one really wants to overcome the crisis to integrate the Eurozone much more. There is also the need, and I agree there very much with George Soros, that the macro-economic policy has to change: The degree of austerity is counterproductive; there is need for structural reforms of course also; and there is need for supply side measures in the Southern countries”, he said.

According to Soros, there has to be a degree of sovereignty sharing in the Eurozone that is considerably more than what existed in the past or exists today.

Soros proposed that going forward, Eurozone should be divided into two groups of countries within the larger European Union: the Eurozone moving towards quasi-federalism with a lot of sovereignty sharing, and then another group of countries, including the United Kingdom, Sweden and others that will remain part of the single market and will participate in common defense and security policy, common foreign service and allowing Europeans to work and live anywhere in the EU. The latter group will, however, not engage in the degree of sovereignty sharing that the Eurozone would.

“This will require a fundamental restructuring and reinvention of the institutions. You already have the Euro Group and ECOFIN of finance ministers. You will need to have a European Parliament that meets, in a way, in two groups : the large European Parliament meeting on the Pan-European Union affairs, and then a smaller version”, Soros suggested.

Speaking of Turkey, he added, “I think in the second group, with Sweden, with Norway, with some others, and with the United Kingdom, there is a place for a very large European country that Turkey is, that can add dynamism, more rapid growth, and more favorable demographic structure to the whole of Europe”.

Nobel Laureate and Co-Chair of the Committee on Global Thought and the Co-Founder, Joseph Stiglitz shared his views on the economic imperatives and said, “Like everybody else I do think the political project was well intended. I will spend most of my time talking about the economics. Economics is the dismal science and Europe is giving us really a field day for depression because Europe is in a recession, and many countries in Europe are in depression and we should be aware of that. If you look at where the GDP is, the declining GDP in Italy, which is not one of the crisis countries, it is as deep as in the Great Depression. There is an enormous amount of destruction of human capital going on. And what this portends for the future of Europe, I think, is not positive”.

Stiglitz stressed that this disaster was man-made and the man-made disaster had four letters : the euro. “The euro project is a great project. But when they went from a political project that had trade, that had an attempt to integrate and create a single market, to create a single currency before the political framework was created, that was what invited the disaster that followed”, he said.

Despite his skepticism, he felt Europe could work. However it would need deeper economic reform than has been talked so far. The fundamental need was for structural reform, but not structural reforms within the European countries instead structural reform of Europe, and of the Euro framework.

“Part of the problem was that before, as the euro was being created there was a failed analysis of what was going to be needed to make this diverse group of countries work. So when you have a misconception at the beginning and a failed misdiagnosis as time goes on, not a surprise that things have not worked out very well. And continually what they say is: we have to have a stronger enforcement, more austerity. Austerity is part of the problem; it is part of the reason that Europe is in a recession now. It is not the solution, it is part of the problem, and this failed mindset is really an inherent part of the difficulty”, Stiglitz argued.

Stiglitz made four recommendations: the first called for further integration, one that requires a fiscal union, in the form of Eurobonds or ECB borrowing.

The second was the need for a banking union. ‘Exacerbating the problem of austerity is that with a single market, money flows around everywhere very easily and money is leaving the banking systems of the countries that are in crisis. Backing any countries’ banks is the country’s government. The credit default swaps of the sovereigns and the credit default swaps of the banks are highly correlated. So as money leaves banks, the banks cannot lend and the country gets further down. So you need a banking union. What you need is common deposit insurance, common supervision and common resolution’, Stiglitz said.

The third recommendation urged for a growth strategy and the fourth insisted on industrial policies to enable countries as divergent as in Europe to ‘catch up’.

“Finally, I agree with Kemal, you need adjustment inside Germany – wage increases. Internal devaluation, which is the strategy that Germany is recommending, forcing the burden on other countries, has never worked. The euro was intended to bring the countries of Europe together; it was a political project. But in fact what it is doing is to divide Europe. And the tensions are very very clearly there, it has been described by the other speakers. There is, right now, as I see it, insufficient solidarity to make it work. So in my mind, to save Europe, to save the European Union, it may be necessary to sacrifice the euro”, Stiglitz asserted.

George Papandreou, former Prime Minister of Greece from 2009 -2011 and a member of parliament since 1981 gained fame as ‘the Prime Minister who implemented austerity measures’. He joined the panelists and explained his point of view, “When I was elected, I was elected on a mandate, certainly not of austerity, but of change. That was the mandate; actually it was a slogan, “either we change or we sink”, which rhymes in Greek. We knew that we really needed deep reform. In the end my first priority became, because of the situation after revealing that our deficit was not 6%, as the previous government had misstated, but 15.6%, that I had to do everything I could to keep the country from bankruptcy and exiting the euro”.

Papandreou while being a pro-European also accepted that not enough had been done so far and there was a lot more work to be done. He, however, maintained his confidence in the collective strength of the European Union.

Papandreou swiftly moved on to clarifying three myths. “The first myth was that this was a Greek problem, so therefore the whole burden of the solution of course would be on Greece”, he said. Papandreou insisted that on looking up the OECD statistics, it was clear that Greeks work the hardest compared to all European Union countries.

The second myth that Papandreou referred to was that even after a year, the Troika – the IMF, the ECB and the Commission, felt that Greece would not be able to access the markets in 2012. “Now, if Greece is the problem, then Greece again is the problem there. Well, so that was another myth. I say it is a myth because again, the OECD in 2012 proclaimed that Greece was the number one reformer amongst all OECD countries”, said Papandreou.

He continued, “So there are issues, which have been mentioned here which need to be seen, first of all, which are not particularly Greek. I do not say we did not have our problems, and I always say that we had our first responsibility to change our country and reform our country”.

Papandreou points out to the other issues with the Eurozone structure, the lack of oversight of the Commission itself; the ECB and its single-mindedness around inflation and employment and the lack of competitiveness with other parts of the world. He points out to the fact that Europe does not have much of a growth policy. He insisted that this is not just an internal problem and one that needs to be worked on together by all the Eurozone countries.

“The final myth is austerity versus reform. I will just read what Martin Wolf said yesterday in the Financial Times: “austerity and reform are the opposite of each other. If you are serious about structural reform, it will cost you upfront money”. Now he was talking about the Eurozone and the austerity programs, and now more money of course would mean more time, would mean more money for reforms”, he said.

According to Papandreou, a more effective political strategy would be to come up with a Eurobond through which one could intervene in the markets. He pointed out to another major flaw, in that, it allowed the market fears to push us around and to dominate the whole political and economic debate.

“Now I would say that of course there is a bittersweet outlook around Europe. There is the good and the bad. First of all, if we look at Europe the bad side, the bitter side is that GDP results are quite dismal. There is no really long-term growth strategy. We are not pooling our strengths as we fear of pooling our risks; and I think we have already pooled our risks, now is the time to pool our strengths, and we would be able to calm the markets and do so in a better way”, said Papandreou.

He continued, “We need the political discourse. Secondly we need a growth strategy. Third, we need a program for the unemployed. We need further integration, which in the end means further centralizing our decision making, whether it is in fiscal policy, banking union, economic, or social policy. But that also means we need to democratize our European institutions. And therefore, we cannot simply hand over to some bureaucracy in Brussels. Finally, I think we need to rethink this whole austerity program and prioritize deep reform”.

Tying together the varied, diverse and constructive recommendations put forth by the members of the panel, Jan Svejanar, Director, Centre for Global and Economic Governance at Columbia University emphasized on the political will to find the right solution.

“My main thesis is that the European Union is likely to survive. I think that the Eurozone also, although with somewhat lower probability. Europe as a whole is rich, and so it is a question of political will to find the right solution. Temporarily the situation has calmed down, which is very good. It gives an opportunity to carry out some of the reforms. The question is will they be carried out? And importantly will growth return? Because right now the situation is very difficult in the sense that the European Union is stagnant economically, and the Eurozone is declining and expected to decline”, Svejnar said.

Svejnar pointed out that the exit by Greece and others was unlikely and that new members would enter into the Eurozone as well as the European Union. He categorized the barriers to the solution as economic, political and social and said, “The austerity is reaching political and social limits in many of the countries. There is economic nationalism in the sense that the rich core countries are unwilling to pay for what they see as the prolificacy of the periphery countries. There is the merciless debt accumulation arithmetic that was mentioned, that as GDP declines, debt over GDP is growing even if debt itself is not growing. So the question is what will happen, and what we see in policy makers in Europe is that decisive steps are deferred unless they are really pressed by a crisis-type situation to take some steps. So I think that is really the weakness right here”.

Svejnar said that there was a possibility of an exit of the United Kingdom from the European Union and referred to it as the big issue that would be forthcoming in the next couple of years. He outlined the German issue – Germans being less willing to subsidize other countries – as the another ‘big’ issue.

“In terms of the future development, I think it is important to realize that Europe has incredible potential. It is a continent, which is the largest economy in the world. Because there are still quite a few inefficiencies, by eliminating those Europe can really move ahead, so it has considerable potential. The problem is the upfront austerity that is facing many of these countries”, he said.

The threats to the instability, according to Svejnar, are related to weak GDP and steps like the downgrade of the UK economy add to the uncertainty and the instability. “Should there be a slowdown in the US or in the world economy, that would have further, unfortunate repercussions on Europe”, Svejnar concluded.

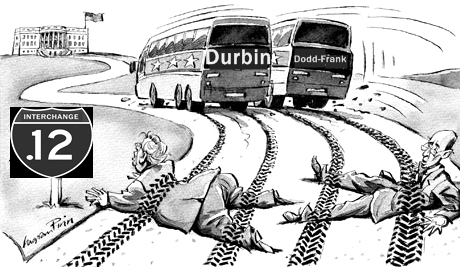

Ridiculing the Fed, Judge Leon pointed out brusquely, “The Fed didn’t have the authority to set a 21-cent cap on debit-card transactions. The Board has clearly disregarded Congress’s statutory intent by inappropriately inflating all debit card transaction fees by billions of dollars and failing to provide merchants with multiple unaffiliated networks for each debit card transaction”.

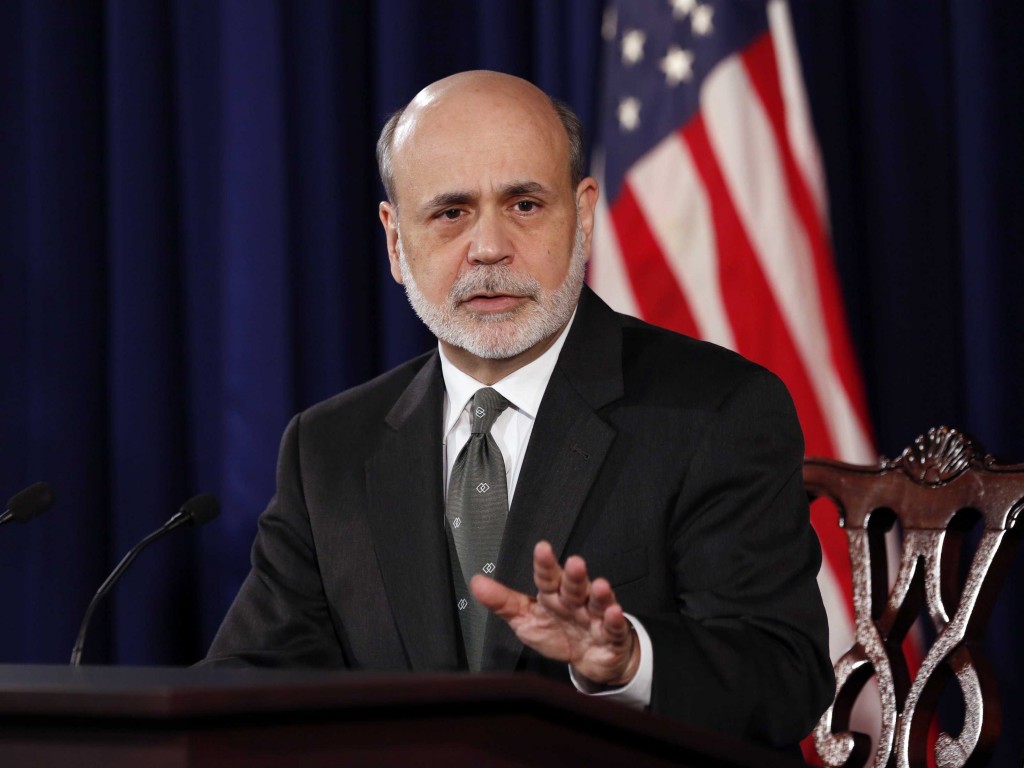

Ridiculing the Fed, Judge Leon pointed out brusquely, “The Fed didn’t have the authority to set a 21-cent cap on debit-card transactions. The Board has clearly disregarded Congress’s statutory intent by inappropriately inflating all debit card transaction fees by billions of dollars and failing to provide merchants with multiple unaffiliated networks for each debit card transaction”. Chairman Ben Bernanke had said on several occasions that he was worried about how the new rule would affect small banks. He maintained the cap aimed to strike a balance between retailers, banks and consumers but left the door open for future changes. “The Fed would continue to monitor the consequences of the new caps and “assess whether the statute and the rule are accomplishing their intended goals”, Bernanke noted in a statement after the Amendment was passed.

Chairman Ben Bernanke had said on several occasions that he was worried about how the new rule would affect small banks. He maintained the cap aimed to strike a balance between retailers, banks and consumers but left the door open for future changes. “The Fed would continue to monitor the consequences of the new caps and “assess whether the statute and the rule are accomplishing their intended goals”, Bernanke noted in a statement after the Amendment was passed.