A regular column on financial payments for Business Wire’s pymnts.com in Boston.

CFPB to police employers over Payroll Cards

Natalie Gunshannon, 27 of Dallas Township, Pa., is a single mother of one daughter. In May 2013, she had just started working at the McDonald’s Restaurant on the Dallas Highway but decided to quit when she received her first pay stub. She didn’t just quit. Gunshannon reached out to an attorney, Mike Cefalo of West Pittston and filed a class action lawsuit in Luzerne County Court against her employer.

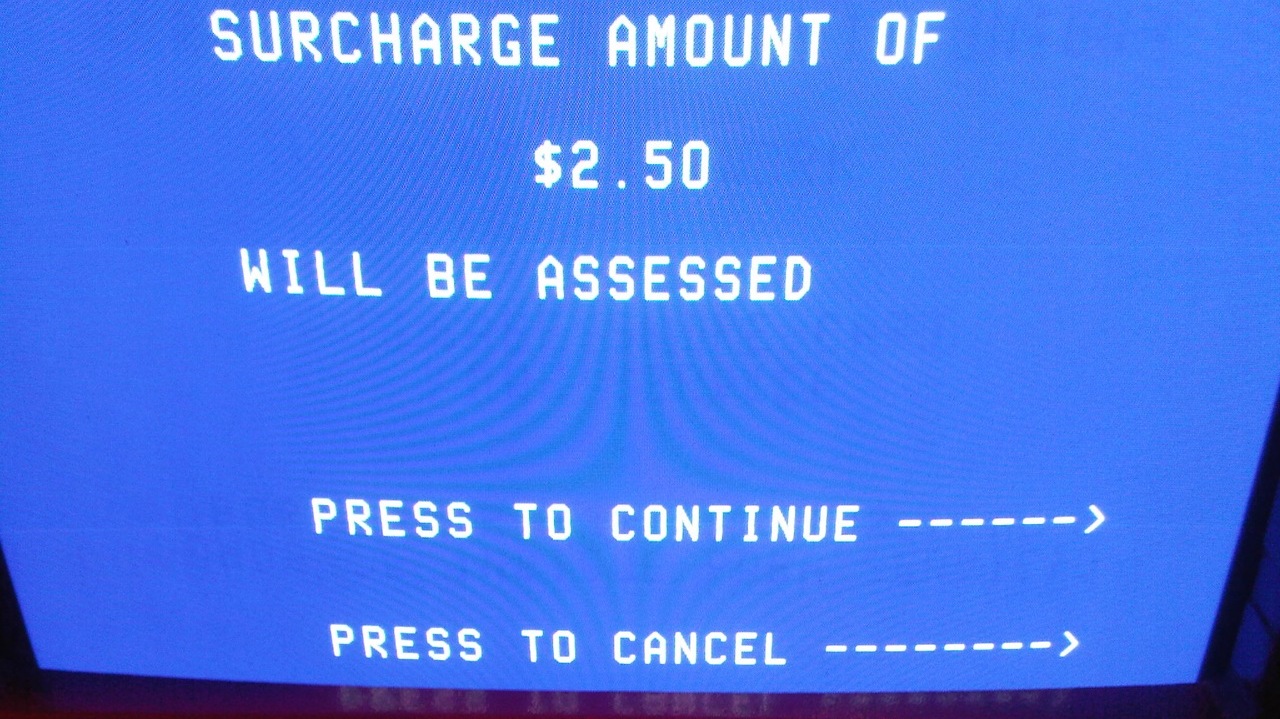

It is not common to walk into an attorney’s office instead of the supermarket upon receiving your hard-earned pay. Gunshannon explained that her first paycheck was enclosed in a Chase Bank debit card with instructions on how to use it and the fees attached. Among the several fees listed on the schedule were a $1.50 charge for ATM withdrawals, $5 for over-the-counter cash withdrawals, $1 per balance inquiry, 75 cents per online bill payment and $15 for a lost/stolen card.

The following day she reached out to her supervisor and asked if she could be paid by check or direct deposit. “No!” was the categorical answer. The card was the only way.

Gunshannon was to make $7.44 per hour, and the minimum wage is $7.25. Now, with the given charges, her hourly wage could even go below the minimum wage. “I need to receive all the money I earn,” she urged her employers. “I can’t afford to lose even a few dollars per paycheck. I just think people should be paid fairly and not have to pay fees to get their wages,” she begged.

The case created a furor around the use of the payroll card. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) sought to address this and on Thursday warned employers against compelling employees to receive wages on payroll cards that have a slew of fees attached. In a published bulletin, the CFPB clarified the federal consumer protections that apply to payroll cards – fee disclosure, access to account history, limited liability for unauthorized use and error resolution rights.

Federal law prohibits employers from mandating that employees receive wages solely through a payroll card. State laws have the jurisdiction to see which alternative payment methods employers can offer.

“Employees must have options when it comes to how they receive their wages,” CFPB Director Richard Cordray asserted in a statement. “Today’s release warns employers that they cannot mandate their employees to receive wages on a payroll card. And for those employees who choose to receive wages on a payroll card, they are entitled to certain federal protections.”

Reports made to the CFPB in recent months over the issue of payroll cards are particularly related to retail and food service industries. Several companies are engaged in paying their workers through payroll cards to avoid the cost of issuing paper checks. Aite Group, a consulting firm specializing in the payments industry, states that the number of payroll cards is rising from 3.1m in 2010 to 5.8m today and is expected to rise to 10.8m in 2017. “Employers this year are expected to load $43b onto the cards, rising to $68.9b by 2017,” Aite revealed.

The cards mean big business for financial services companies, including banks and card networks – Visa and MasterCard. First Data Corp. is one of the biggest industry players and operates payroll card programs that are issued by banks.

Responding to the controversy around payroll cards, Mark Putman, Senior Vice President of First Data’s prepaid solutions, said, “Consumers need choice and this guideline is one of the pillars of our program. CFPB’s guidelines reiterate practices we have a history of following.”

In an emailed statement, the CFPB reasserted its regulation of employers over violations of payroll cards, stating, “The bureau intends to use its enforcement authority to stop violations before they grow into systemic problems, maximize remediation to consumers, and deter future violations.”

However there is another side to this coin. For employees who are unbanked, payroll cards can indeed be an inexpensive alternative. Unbanked employees may end up paying far more to cash a check at Walmartor at a check cashing point or may incur additional costs when they pay a bill online through a third party like Western Union.

If the unbanked employees open a bank account, for example a Bank of America account, they will incur a monthly charge of $10 -$14 and may risk being charged overdraft fees, not to mention paying $2.50 if they take cash from an ATM not operated by Bank of America. The costs involved in using payroll cards, as compared to the costs of using alternative means of pay, might be lesser and this method may end up being the more affordable option for many employees – but that may not always be the case.

“In general, payroll cards can be a useful way to pay employees who don’t have bank accounts, who can’t have direct deposit,” explained Lauren Saunders, Managing Attorney at the National Consumer Law Center. “For an employee who doesn’t have a bank account, a well-designed payroll card can be a fast, convenient and inexpensive way of getting your money but in practice, the cards can hit workers with a fusillade of fees that substantially cut into their wages, including monthly maintenance fees, point-of-sale fees, ATM fees and even overdraft fees,” she added.

In an attempt to bring clarity to the glaring question of whether payroll cards could work well for employees, the Consumer’s Union clarifies some of the aspects in a report. Card programs vary widely in terms of cost, convenience and level of consumer protection and it is important to make the right decision over the payroll card program employers choose.

The report recommends that employers choose a reliable payroll card vendor to avoid the risk of employees losing money if the payroll card issuer goes out of business and to ensure the contract with the issuer requires consumer protection and negotiate the possibility of no monthly fees. It urges employers to identify and restrict the fees such that the card becomes the first step towards financial stability for employees.

Above all, it recommends giving employees a choice. Employees must be offered a choice of receiving a paper check.

To draw an absolute judgment on whether payroll cards are a good means to earn pay or not would be unfair, since it depends on whether the consumer is banked or unbanked and if the alternatives open to a respective consumer would cost any less.

—

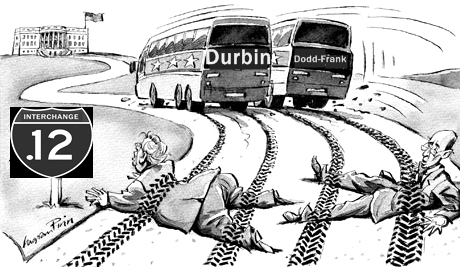

Next Steps in the Durbin Litigation

On 31st July, 2013 the District of Columbia trial court invalidated the Federal Reserve Board’s Durbin regulation, suspending the swipe fee regulation in a cloud of open-ended questions. In an exclusive interview with PYMNTS.com, Ronald Mann, Albert E. Cinelli Enterprise Prof. of Law, Co-Dir. Charles E. Gerber Program in Transactional Studies at Columbia Law School, elaborates on the next steps in the NACS regulation.

KMK: Ron, this invalidation has left the payments community with a number of open-ended questions. How do you see the future proceedings shaping up?

RM: The district court vacated the existing regulation, but stayed its order, so the current status is that the Board’s regulation remains in force for the time being, despite the court’s conclusion that it is invalid. Essentially, that leaves the Board obligated to produce a new regulation on a schedule with sufficient promptness to satisfy the Court. Whether the new regulation will be preceded by notice and comment will be a decision for the Board, though given the complexity of the issues and the stark changes from the Board’s existing interpretation a renewed comment period seems likely.

KMK: There is a lot of speculation around how the Board is likely to react if the course of action the court suggests is unacceptable to the Board. What do you think is likely to happen on appeal?

RM: So assuming that course of action is unpalatable to the Board, the Board’s appeal would go to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, which sits in Washington in the same building as the District Court. The timing of that appeal is difficult to predict, though it seems most unlikely it would be completed in less than a year. And even then, if the Board lost it well might seek review in the Supreme Court. Even with the shrinking docket, there is always a reasonable chance the Court would review a decision invalidating a regulation of this significance.

KMK: What will be the key question on this appeal, if the Board presses ahead for one?

RM: It will be to balance statutory text against deference to agency expertise. It is hard to challenge the view that the statute is poorly drafted, and that the Board was hard-pressed to design a regulation that was both practical and consistent with the statute. The district court’s broad conclusion that the regulation was inconsistent with the statute surely reflects the fact that the litigation here was between the retailers and the Board, with the banks not directly present to explain their side of the matter. It is always difficult to predict how the court of appeals will receive this kind of case, but my sense is that it is quite a difficult one, so that the result on appeal is most uncertain.

—

Rejection of Fed Interchange Fee Caps Roils Debit Business

“We urge the Federal Reserve to pursue all legal means to mitigate the harm this decision will cause to consumers, community banks and all institutions that provide financial services to local communities. The Durbin Amendment and the court’s interpretation will have disastrous consequences for the institutions affected and the communities they serve. This result must be reversed”, Frank Keating, President of the American Bankers Association, said in response to U.S. District Judge Richard Leon’s rejection of the Durbin Amendment, yesterday morning.

Ridiculing the Fed, Judge Leon pointed out brusquely, “The Fed didn’t have the authority to set a 21-cent cap on debit-card transactions. The Board has clearly disregarded Congress’s statutory intent by inappropriately inflating all debit card transaction fees by billions of dollars and failing to provide merchants with multiple unaffiliated networks for each debit card transaction”.

Ridiculing the Fed, Judge Leon pointed out brusquely, “The Fed didn’t have the authority to set a 21-cent cap on debit-card transactions. The Board has clearly disregarded Congress’s statutory intent by inappropriately inflating all debit card transaction fees by billions of dollars and failing to provide merchants with multiple unaffiliated networks for each debit card transaction”.

In his 58-page ruling Judge Leon argued that the cap must go lower, cutting deeper into the $16 billion dollars in revenue that large banks usually reap from the fees. “The Fed’s current implementation of the Durbin amendment has cost banks about half the $16 billion they once made from debit-card swipe fees each year. They take in an estimated $40 billion from credit card swipe fees, which are unaffected by the Fed rule”, Madeline Aufseeser, Senior Analyst, Aite Group LLC, calculated. She added, “If the Fed responds to the ruling by reverting to its original proposal of 12 cents per transaction, revenue for the top 50 credit-card issuers who use Visa and MasterCard networks and have assets over $10 billion would drop to $4.3 billion per year.”

Visa, the dominant player setting the interchange fees, saw its share price plunge the most since December 2010, falling as low as 10.7 percent in New York trading and closing down 7.5% at $177,01. The same shares shot up more than 10 percent, topping the S&P 500, after the final cap was unveiled in 2011 and surprised the business by being almost twice as high as the Fed’s earlier draft proposal.

Judge Leon warned, ‘The Fed has months not years to re write the rule in the light of this decision’.

A central argument that encompasses this debate is that swipe fees, under the Durbin Amendment, must be “reasonable and proportional” to the incremental cost of a transaction. The Dodd-Frank legislation which adopted the Durbin Amendment does not clarify whether the caps should reflect ‘other costs’ incurred by card issuers. The banks hence press for the caps to rise to reflect other costs.

Judge Leon argued that the Fed wrongly interpreted the statue on these costs. “The Fed decided the statute was silent on what other costs could be included in the calculation, and then moved to resolve that ambiguity by including those other costs. How convenient,” Leon remarked. “The statute and the legislative history demonstrate that Congress intended the swipe fee caps to reflect only the costs associated with an individual transaction, not any other costs”, he remarked.

He further added in a statement, “The Fed’s 2011 decision to bend to the lobbying by the big banks and card giants cost small business and consumers tens of billions of dollars and did not do enough to rein in the anti-competitive, anti-consumer practices of Visa and MasterCard”.

In November 2011, National Retail Federation, the Food Marketing Institute and NACS, formerly the National Association of Convenience Stores filed a lawsuit stating the merchants would be substantially harmed by the fees the Fed set under the Durbin Amendment. “The board’s final rule permits banks to recover significantly more costs than permitted by the plain language of the Durbin Amendment and deprives plaintiffs of the benefits of the statute’s anti-exclusivity provisions,” the retailers argued in their complaint.

Refuting the retailers claim, Senator Durbin insisted that small businesses and their customers will be able to keep more of their own money as a result of the amendment and it would make sure businesses would grow and prosper. ‘This is vital to putting our country back on solid economic footing’, he said in a statement.

Citing a recent push by European Union to cap the charges, Mallory Duncan, Senior Vice President and General Counsel of the National Retail Federation, which brought the case, pointed out that opposition to swipe fees is growing world-wide, “The rest of the world is beginning to understand that this is a game Visa, MasterCard and the banks are playing,” she said in an interview.

The law may have been squarely aimed at big banks, but small banks have paid a price in the bargain.

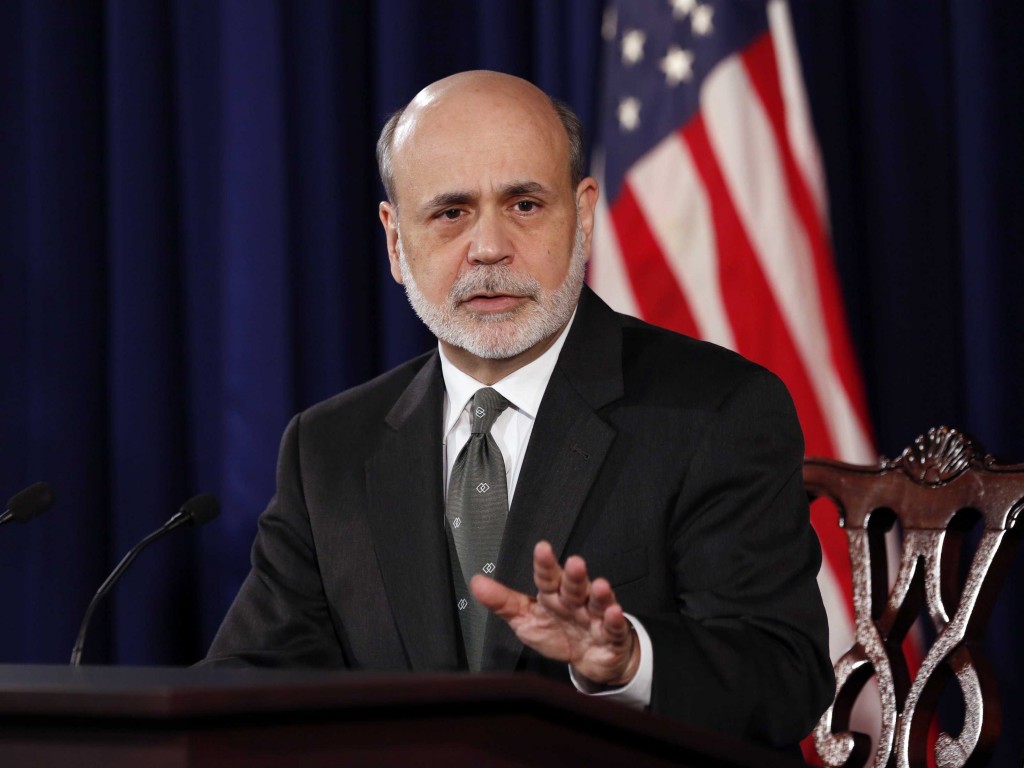

Chairman Ben Bernanke had said on several occasions that he was worried about how the new rule would affect small banks. He maintained the cap aimed to strike a balance between retailers, banks and consumers but left the door open for future changes. “The Fed would continue to monitor the consequences of the new caps and “assess whether the statute and the rule are accomplishing their intended goals”, Bernanke noted in a statement after the Amendment was passed.

Chairman Ben Bernanke had said on several occasions that he was worried about how the new rule would affect small banks. He maintained the cap aimed to strike a balance between retailers, banks and consumers but left the door open for future changes. “The Fed would continue to monitor the consequences of the new caps and “assess whether the statute and the rule are accomplishing their intended goals”, Bernanke noted in a statement after the Amendment was passed.

Leon’s ruling echoes the voices of the retailers that have been fighting against the law since November 2011.

—

US Judge rejects Fed’s Durbin Amendment

‘The Fed didn’t have the authority to set a 21-cent cap on debit-card transactions’, U.S. District Judge Richard Leon in Washington, rejected the Dodd-Frank imposed rules governing ‘swipe fees’, in a ruling today morning.

In his 58-page ruling, Leon asserted, “The Board has clearly disregarded Congress’s statutory intent by inappropriately inflating all debit card transaction fees by billions of dollars and failing to provide merchants with multiple unaffiliated networks for each debit card transaction”. The rule would however remain in place pending new regulations or interim standards.

In his 58-page ruling, Leon asserted, “The Board has clearly disregarded Congress’s statutory intent by inappropriately inflating all debit card transaction fees by billions of dollars and failing to provide merchants with multiple unaffiliated networks for each debit card transaction”. The rule would however remain in place pending new regulations or interim standards.

Visa -9.91(-5.18%), one of the predominant players setting the interchange fees, saw its share price plunge as news of Leon’s ruling hit the markets. The same shares shot up more than 10 percent, topping the S&P 500, after the cap was unveiled in 2011.

The Durbin Amendment that approved a 21-cent limit on swipe fees – half of the average swipe fee of 44 cents – went into effect on October 1st, 2011. It was slammed on the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act at the eleventh hour in an attempt to move a step closer to the retailers’ legislative agenda. Instead, it ignited a spark of unrest among varied stakeholders of the financial services industry.

In November 2011, National Retail Federation, the Food Marketing Institute and NACS, formerly the National Association of Convenience Stores filed a lawsuit stating the merchants would be substantially harmed by the fees the Fed set under the Durbin Amendment, a provision of the Dodd-Frank legislation. “The board’s final rule permits banks to recover significantly more costs than permitted by the plain language of the Durbin Amendment and deprives plaintiffs of the benefits of the statute’s anti-exclusivity provisions”, the retailers argued in their complaint.

Refuting the retailers claim, Senator Richard Durbin insisted that small businesses and their customers would be able to keep more of their own money as a result of the amendment and it would make sure businesses would grow and prosper. ‘This is vital to putting our country back on solid economic footing’, he said in a statement.

The law may have been squarely aimed at big banks, but small banks have paid a price in the bargain.

Chairman Ben Bernanke spoke on several occasions expressing fear about how the new rule would affect small banks. He maintained the cap aimed to strike a balance between retailers, banks and consumers but left the door open for future changes. “The Fed would continue to monitor the consequences of the new caps and assess whether the statute and the rule are accomplishing their intended goals”, Bernanke noted in a statement after the Amendment was passed.

Leon’s ruling today echoes the voices of retailers who have been fighting against the law since November 2011.

—

CFPB tangles with Bankers over Big Data

“Do they need the reams and reams and reams of data we’re having to provide to them? Don’t we have to find a healthier balance here?” Susan Faulkner, Senior Vice President, Bank of America, implored at the Conference of Consumer Bankers Association in Phoenix, early this year.

Faulkner is not alone in her plea. Bankers across the industry find the information gathering by the CFPB a vexing new regulatory burden. It adds another layer of bureaucracy to U.S. banking regulation, in their view. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce in a letter to Richard Cordray, Director, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, charged the CFPB with misusing the regularly scheduled examinations of banks to demand huge amounts of data requests that instead should be made by rule or order. David Hirschmann, Head of Chamber’s Centre for Capital Markets Competitiveness hollered, “Bureau’s data requests have been often unfocused, overly inclusive and not coordinated with other regulators.”

Richard Riese, Senior Vice President, Centre for Regulatory Compliance at American Bankers Association has taken a more optimistic view and noted, “The bureau’s examiners are new to the field and over time will learn to be more focused. I think both sides will evolve in the process and we’ll get to some efficiencies.”

Two sources, on condition of anonymity, said that the procedures used by the Consumer Bureau are far different from those typically used by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. While the two regulators have seldom deviated from using consumer finance examinations at larger banks, the consumer bureau demands data from multiple banks on grounds of consumer-protection issues even if the issue arises in a single institution.

If you’ve reached this point in the column you probably have a burning question: What kind of data is the CFPB collecting that has the potential of infuriating so many in the banking community?

Good question.

One hundred thousand negative reports have been filed so far with the Consumer Bureau against banks; close to 450 companies are being closely watched as a result of the complaints, anonymous information of about 10 million consumers is being thwarted; a deep repository of consumer finance data, including credit card information and checking account overdrafts from nine banks is being created; records of credit card add on products – credit monitoring and debt cancellation are being collected; a mortgage database with Federal Housing Finance Agency that will integrate consumer credit information with loan and property records is being built.

While Mr. Snowden would not be impressed, it is this overwhelming list that has provoked the ire of banking executives.

The mining of such massive pools of information ought to bring questions of privacy into the picture.

“Any agency compiling massive amounts of data has to consider that you can use bits that are not personally identifiable and put them together,” David Jacobs, Consumer Protection Counsel, Electronic Privacy Information Centre, said in an interview. He further explained that by aggregating information it collects or buys, the bureau complies with federal privacy laws. It will have to ensure that data it releases doesn’t add up to a fuller picture.

Sendhil Mullainathan, Former Assistant Director for Research at the Consumer Bureau and Professor of Economics at Harvard University, in an interview with Bloomberg argued that researchers have no interest in specific individuals. “No researcher needs to know about any one person,” he said. “Just the opposite. They need to know about thousands of people.”

He further asserted, “The agency is committed to protecting the privacy of consumer information and doesn’t collect personally identifiable data such as social security numbers. It’s credible to say that within the next year, CFPB will be the best place for consumer finance data.”

Joan Claybrook, former Head, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration compared the CFPB’s data collection efforts to the transport agency’s early warning database on auto safety defects that in her view helped warn against fatalities.

Making an argument for data collection, Mullainathan, argued, “The consumer bureau should play the kind of role in consumer finance that the Federal Reserve does in macroeconomics, continually collecting unemployment data so analysts can dive deeper into the subject at any time.”

In a recent hearing on Tuesday, 9th July, before the House Financial Services Committee, one of CFPB’s top official was asked to specify the number of Americans the agency had gathered the financial data on. The official failed to put a precise number to the question and in the bargain earned the skepticism of the committee. Furthermore, with its enthusiasm around publicizing consumer complaints, the CFPB is being seen as an adversarial regulator.

“To me the bottom-line around any questions surrounding the CFPB is that, CFPB is supposed to be an evidence-based policy maker and rule maker and one of the necessary inputs for doing evidence based policy making is data. I am not saying it’s efficient but it is a necessary input”, reasoned Jonathan Zinman, Academic Director, US Households Finance Initiative, in an interview with PYMNTS.com.

He further argued that the point in question is whether the CFPB is collecting any data or asking financial institutions for data that they don’t necessarily need to supply to other regulators. “That seems like a germane question to me. Is CFPB actually increasing the regulatory burden of such institutions?”

Zinman further pointed out that with regard to compliance and reporting costs, CFPB would only be adding to reporting costs if it is asking for data that the financial institutions are not already providing to other regulators.

Katherine Porter, Professor of Law at University of California spoke to PYMNTS.com and explained that the CFPB is currently getting data from several places and how we think about relative costs and benefits depends on what we are talking about. She reasoned, “So if it [CFPB] is buying the same data as the industry buys and the capital market buys then I think it is good. I think being a supervisory body and supervising is a rigorous process. This is an industry where we want to see that consumers are being protected, laws are being followed and capital markets are stable. Data collection as a part of that can help the CFPB better understand the business that it is supervising.”

“You cannot study consumer credit in a vacuum. Data collection gives the context to interpret what’s going on”, she asserted.

—

Bitcoin, in search of a legal status

“Bitcoin is not the only digital currency, nor the only successful one. Gamers on Second Life, a virtual world, pay with Linden Dollars; customers of Tencent, a Chinese internet giant, deal in QQ Coins; and Facebook sells Credits. What makes Bitcoin different is that, unlike other online (and offline) currencies, it is neither created nor administered by a single authority such as a central bank”, The Economist recorded in its report on Mining Digital Gold, on 13th April earlier this year.

Bitcoin is a virtual currency used as a form of payment with a decentralized system and without a central issuer. Neither does it require the endorsement of any authority to open an account or make a transaction, nor does any authority have the power to confiscate Bitcoins or prevent users from transacting. A peer-to-peer computer network made up of users’ machines, similar to a file-sharing system and the audio-visual chat service, Skype underpins it. The computers mathematically generate the virtual currency through a procedure called mining, a number crunching task that makes it progressively difficult to mine Bitcoins over time and limits the total number that can be mined in a day to around 21 million. It is set up to sort of simulate gold, which is similarly limited in quantity and increasingly scarce. This in a gist, explains the fundamentals of Bitcoin.

After starting in 2010, Bitcoin has earned several advocates by 2013. Michael Sivy, a Chartered Financial Analyst and a former securities analyst for an independent stock research firm noted in his column, The real significance of the Bitcoin Boom and Bust, for Time, “The scale of the recent boom-and-bust has been staggering indeed. At the start of the year, a Bitcoin was worth $13.51. Earlier this week, it traded as high as $266. And on Thursday, it plummeted to less than $100, as one of the exchanges where Bitcoins are traded closed temporarily. This would be comparable to the exchange rate for the British pound soaring from $1.62 (where it was on Jan. 1) to $31.90 and then falling back to $12.”

The creation and transactions of Bitcoin are controlled by a concept called crypto-currency that standardizes, protects and promotes the use of Bitcoin money. The Bitcoin Foundation further elaborates, “As a non-political online money, Bitcoin is backed exclusively by code. This means that— ultimately—it is only as good as its software design. … Cryptography is the key to Bitcoin’s success. It’s the reason that no one can double spend, counterfeit or steal Bitcoins. If Bitcoin is to be a viable money for both current users and future adopters, we need to maintain, improve and legally protect the integrity of the protocol.”

The departure from central banks and monetary authorities makes Bitcoin an interesting option for those who fear the aggressive expansionary policies of the central bank. In an interview with The Telegraph in the UK, Warren Buffett condemned Bernanke’s monetary policy and pointed out that those who parked their money in cash equivalents or short term US Treasuries had missed the party over the last nine months as Wall Street rocketed to all-time highs. “It’s brutal. I don’t know what I would do if I were in that position”, he told Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, International Business Editor at The Telegraph.

Weak support for the central bank’s position on monetary policy through the ongoing financial crisis has lead to increased demand for gold and other ‘safe havens’ and a fertile ground for “virtual gold” to take root. “Bitcoin, rather than fixing the value of the virtual currency in terms of those green pieces of paper, fixes the total quantity of cyber currency instead, and lets its dollar value float. In effect, Bitcoin has created its own private gold standard world, in which the money supply is fixed rather than subject to increase via the printing press”, Paul Krugman, Economist and Professor at Princeton, noted in his column, Golden Cyberfetters. Of course, unlike gold, which has a natural limit, Bitcoin ultimately follows rules set by humans it would seem.

The payment system in Bitcoin involves reallocating a coin in the various registers from the payer to the payee. Each user has an electronic wallet and a key pair that does not require identification by any national regulator or financial institution. It is attractive for those that prefer anonymity whether for political reasons or for criminal activities. Just like cash, except its electronic.

Among the less-attractive features of Bitcoin is that transfers in the Bitcoin system are irrevocable and the wallet and key pair is the only way to access Bitcoins. If the key pair is lost, the coins are inaccessible and are lost. While the Bitcoin transaction is free, the users pay to acquire Bitcoins either from an intermediary or through a market. There might be a commission involved or a fee to complete the transaction.

Bitcoin also does not support any central registers to record the transactions. Instead, there are a series of records, synchronized across a peer-to-peer network, of the entire history of Bitcoin transactions that can be used to check which wallet and key pair a given coin was last transferred. A large number of copies of the register are kept across the network and this proves helpful since there is little incentive or gain for any particular register keeper to falsify the record. In addition, creating a false competing record of equal or longer detail than the others can be mathematically very difficult. However, an inherent risk is that the number and quality of record keeping nodes are likely to diminish over time since the voluntary register keepers will get tired of the effort involved and for-profit nodes will become uneconomic as the mining of coins becomes harder.

The wiki page on Bitcoin suggests that the protocols and rules underlying Bitcoin are public domain. Security is not based on secret codes and protocols or private networks but a distributed system that makes fraud difficult and uneconomic. However, it also accepts that a flaw in the protocols may be discovered at a future time allowing for additional coins to be created or the transaction record to be surreptitiously altered.

Currently several questions around the legality of Bitcoins, or at least how they are being used, are being raised.

Circulatory property rights sits on top of the list. Unlike other forms of intangible private property, Bitcoins are not recognized by any international treaty or domestic legislation. This undermines its legal status. Additionally, there is not a clear issuer or party responsible for creating, distributing and honoring Bitcoins. The Bitcoin Foundation oversees this, where a loose collection of individuals operate the system. Unlike most payment systems, the participants are not bound by a set of central rules.

“At their core, most payment facilities rely on contracts to set out the rights and responsibilities of each party. Legislation, common law and industry codes also have some impact. That is, the contracts do not set out exhaustively the rights and responsibilities of each party. Alan Tyree, at the University of Sydney, Faculty of Law, elaborates on the ambiguity of the participants’ roles and responsibilities.

Besides cash, currently most payment facilities operate on the basis of accounts kept by trusted intermediaries. There are however differences in the character of more centralized payment facilities like cheque accounts and less centralized facilities like anonymous smart cards. Different regulatory and policy issues are also likely to arise with different payment systems. Bitcoin is a decentralized account based payment system without an issuer or central counterparty that involves the circulation of valuable rights transferred irrevocably by electronic order.

Regulatory issues embracing Bitcoin range from financial services regulation and banking regulation to currency regulation and legal tender. The United States has a complex and fragmented legal framework and regulatory structure governing payment services. Article 4A of the Uniform Commercial Code, adopted by most US states, regulates various issues of non-cash payments, the revocability of payments and the rights and obligations of funds transfer. The Official Commentary on Article 4A however also states that it is deliberately limited to funds transfers through the banking system and excludes payments via remittance dealers and other arrangements. This implies that is does not include virtual currencies like Bitcoin.

The US Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Unit (FinCEN), in its Application of FinCEN’s Regulations to Persons Administering, Exchanging, or Using Virtual Currencies, suggests that persons carrying on a business of brokering Bitcoins or running an organized exchange will be regulated as financial services firms, but not the user.

Bitcoin participants may not require licensing under the US banking regimes but taking deposits and making loans denominated in Bitcoin currency will call the attention of US regulators. Another compelling point of contention in the regulatory space around Bitcoins is that they are not legal tender and are unlikely to be so in the short-medium term.

Several aspects of Bitcoin stand in question and its long term viability is debatable but it has proved the concept of a decentralized non-issued electronic currency and has given reason to believe that virtual currencies could have a future. At present, the commercial and contractual laws that apply to financial intermediaries and market operators will apply to participants of Bitcoin.

Ryhs Bollen, Senior Associate at RMIT University, Australia, in his paper, Best practice in the regulation of non-cash payment services, argues that a well designed and proportionate legal and regulatory regime will support user confidence in, and therefore growth of, innovative payment systems such as virtual currencies. Supporting Bollen, Supriya Singh, Faculty at RMIT University, in her research, Designing for Money across Borders, puts it articulately, “There is nothing inherent in a piece of paper, a plastic card or electronic information that converts it into money. Money is money only when it is trusted that it will be honoured in your networks of use and exchange. Creating and protecting trust therefore becomes a crucial issue in the regulation of payment services.”

—

The Fire that Durbin Amendment lit, never doused

The Durban Agreement and the Durbin Amendment have one thing in common. They are both working towards an ideal climate. The former regulates carbon emissions and hopes to reach a global climate agreement; the latter regulates interchange fees and hopes for a universal agreement on a fair climate for financial services.

Signed into Law on July 21, 2010, the Durbin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act, introduced by Sen. Richard J. Durbin, ignited a spark of unrest among varied stakeholders of the financial services industry. The amendment was slammed on the Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act at the eleventh hour in an attempt to move a step closer to the retailers’ legislative agenda. This year, the amendment completes its third year.

Through this amendment, the Federal Reserve decided to reduce the fees that merchants pay banks when consumers use their debit cards. It was entitled as ‘Reasonable Fees and Rules for Payment Card Transaction’ and prescribed standards for ‘reasonable’ interchange fees, that are payable to certain debit card issuers.

In a statement that Wednesday morning in 2010, Sen. Durbin said, “Small businesses and their customers will be able to keep more of their own money.” He added, “Making sure small businesses can grow and prosper is vital to putting our country back on solid economic footing.”

In essence, the Amendment pits two critical players in the financial battlefield against each other – businesses and banks.

Payment services companies, the two predominant players being – Visa and MasterCard, set the interchange fees, but financial institutions that issue the debit cards reap most of the gains generated from the fees. American businesses, as a result, are forced to pay high debit interchange fees, reducing their profit margins and leading to higher retail prices for consumers.

Payments service companies only earn a percentage of each transaction they facilitate but the more debit cards are issued, the more profits they earn. Here, a good bait for the payments services to throw at financial institutions is to offer the highest interchange fees, since it will bring the highest return for banks.

Note here, that by setting a higher interchange fee, the purpose of the payments service companies is to win banks, not necessarily consumers.

This partly explains the highly uncompetitive payments services market where 80% of electronic transactions are dominated by Visa and MasterCard. National electronic service companies like PayPal and Discover have made significant attempts to break through this monopoly, but it continues to remain a work-in-progress.

Section 1075 of the Dodd-Frank Act, which is the Durbin Amendment, added a new section 920 to the Electronic Fund Transfer Act (EFTA). The new section seeks to define an amount of interchange fee that is reasonable and proportional to the cost incurred by the issuer. It charges the Fed with the duty to oversee the debit interchange rates are directly related to the debit transaction costs.

In its most recent study, the Fed capped debit interchange fees for large banks at twelve cents, substantially lower than the national average of 44 cents per debit transaction. This is likely to result in a loss of billions for American banks.

There is some solace however for banks and credit unions holding under 10 billion dollars in consolidated assets. The Durbin Amendment exempts them. This exemption is viewed by some as a political act to go after large banks that receive billions of dollars of taxpayer’s money.

Besides cracking down on big banks, the amendment also intends to infuse more competition into the electronic payments services industry. The underlying goal being that more competition will lead to lower interchange fees. The Amendment requires issuers to issue debit cards of atleast two unaffiliated networks. Unlike the exemption on interchange fees, there is no exemption on this for small banks and credit unions.

Sandwiched between the payment services companies and the big banks, the merchants have struggled over the years to raise their profit margins from retail sales. The Durbin Amendment took recognition of that and explicitly allowed merchants to offer discounted prices for certain types of financial transactions and even refuse to accept debit cards for small purchases. This is a welcome relief for small business, that most often suffer the impact of interchange fees, due to the lack of economies of scale.

Meanwhile, the fierce fight continues between the banking institutions and businesses.

Banks accuse the Durbin Amendment for allowing a way for avaricious businesses to earn more profit at the expense of community banks and consumers; businesses argue and charge the amendment for allowing Wall Street executives to earn more profit at the cost of small businesses and consumers.

In a Senate Banking Committee, Sheila Blair, Chairman at Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, remarked, “the likelihood of this hurting community banks and requiring them to increase the fees they charge for accounts is much greater than any benefit retail consumers may get.”

The question looms large: Is this Amendment really just a mere transfer of wallets from big bankers to big businessmen?

On May 23, 2013, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve released an analytical study on the Impact of Regulation II on Small Debit Card Issuers. This study draws on Regulation II of the Durbin Amendment that makes it mandatory for every debit card issuer, irrespective of size, to have at least two unaffiliated networks on every debit card.

While small debit card issuers are exempt from the Durbin amendment on interchange fees, they are not exempt from network exclusivity. The point of contention here is that networks do not establish separate interchange fee for exempt issuers, thus undermining the effectiveness of such an exemption.

The study highlights three issues in particular. One is the issue of having separate interchange fee schedules for exempt and covered issuers. It was observed in 2012, that networks provided a higher average interchange fee to exempt issuers than non-exempt issuers. The second issue at hand looks at the change in exempt-issuer interchange fees since the implementation of interchange fee standard on non-exempt issuers. It highlights that in 2009, the average interchange fee for all issuers was 43 cents. “For the first three quarters of 2011, before the interchange fee standard took effect, exempt issuers received an average of 44 cents per debit card transaction. The average interchange fee per transaction received by exempt issuers has returned to the 2009 level of 43 cents since the implementation of the interchange fee standard”, the study reports.

The third issue relates to changes in exempt-issuers’ interchange revenues. In 2012, the exempt issuers received $7.4 billion in total debit card interchange revenue, compared with approximately $5.3 billion in debit card interchange revenue in 2009, according to the study.

Some of the other issues pointed out by the study are the evidence of discrimination against cards issued by exempt issuers and the cost to small issuers of adding a second unaffiliated network. While the Fed conducted a survey with the community commercial banks, credit unions and thrifts, the responses were voluntary and conditioned on the willingness and ability of participants. Hence they cannot be considered representative of the overall experience of small issuers but they do highlight that the regulation has had potential effects on small issuers.

To seek further clarity of the impact of the amendment on banks, issuers and consumers, several economists are still conducting research. According to one such study that is still a work-in-progress, it has been observed that the overall interchange reduction increased the market capitalization of merchants by a far greater margin than it decreased the market capitalization of banks. It was also noted that the cost to merchants for taking payments on debit cards declined while the effective cost to issuers for providing debit card services to consumers increased by a corresponding amount.

The critical question is whether consumers gained more from cost savings passed on by merchants in the form of lower prices and better services, than what they lost from cost increases passed on by banks, in the form of higher prices or less service. Some economists estimate that the consumers lost more on the bank side than they gained on the merchant side.

In the fourth quarter of Economic Review 2012, Fumiko Hayashi in his report titled, ‘The New Debit Card Regulations’, concluded that the regulatory and legal changes imposed on the debit card industry had diverse effects, with several distinct implications for market competition among card networks and card-issuing banks.

“Most card networks have set two separate interchange fee schedules: one for regulated banks, conforming to the new caps on interchange fees for those banks, and a separate one for exempt banks. Although the card networks can still set interchange fees as they see fit for exempt banks, the regulatory and legal changes have created new incentives that exert downward pressure even on the exempt banks’ fees”, Hayashi revealed.

On observing the changes in market shares among debit card networks over the past two years, competition had risen among debit card networks. A good example of increased competition among the network for merchants is the decline of Visa’s market share, especially in the PIN debit card market.

“Regulated banks have seen their interchange fee revenues fall while exempt banks’ revenues have remained roughly the same, on average. Regulated banks’ new incentives are likely to drive marked changes in their product promotion efforts as they encourage customers to shift from signature debit to PIN debit and from debit card use to other payment methods”, the report stated.

Among some anticipated consequences is the propensity of competition to rise between the regulated and exempt banks and within the exempt group. The nature of competition within the regulated banks has changed as a result of the amendment but whether that is likely to rise is yet to be established. According to Hayashi, “Regulated banks may no longer seek to attract customers by offering rewards, but they now have more incentive to compete for customers by reducing or eliminating the fees associated with checking accounts and debit cards”.

By raising the level of competition among card networks and by shrinking the fees charged to merchants, the regulators seem satisfied with their interventions. What unnerving for the rest of us is the unintended consequences.

—

Regulators stab Deloitte : Beware! Banks, Consultancies

“People want to know that regulators are looking out for the American public, not the banks,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D. Mass asserted at the Senate Banking subcommittee hearing on April 11, 2013. The agenda was to review banks’ use of independent consultants to complete the foreclosure review. Instead, the hearing whipped the regulators.

Warren wasn’t alone in her indignation. Sen. Sherrod Brown, chairing the financial institutions subcommittee hearing, argued that regulators had failed to identify uniform standards governing their actions.

Clearly, the hearing had gone awry. Officials from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Federal Reserve Board soon came to the realization that the complexity of the undertaking had been greatly underestimated. One close look at the number of institutions, the number of consultants, the number of borrowers and the number of decision points involved in the hearing will give anyone a rough estimate of the unusually complex task, the committee was faced with.

“Why didn’t the OCC handle the loan reviews itself instead of forcing banks to hire their own consultants?”, Sen. Jack Reed, D-R.I. questioned the regulators, urging them to hire their own consultants. “I think you’ve got to have a new process. And I think if the process requires modification of federal rules and regulations, then that’s something the OCC and the Fed should immediately demand of us. Because essentially what you describe is a core activity of the OCC — stopping the wrongdoing of regulated institutions and protecting consumers”, he added.

In response, Daniel Stipano, Deputy Chief counsel at the OCC appealed to the lawmakers to give the OCC the power to seek sanctions against independent contractors.

Two months and a week later, the New York State Department of Financial Services declared that it is fining Deloitte Financial Advisory Services $10 million as part of a settlement stemming from its anti-money laundering advisory work with Standard Chartered bank. In addition, the regulator banned Deloitte from working for New York – chartered banks for one year. The consulting firm was also found guilty of disclosing confidential information about other clients to Standard Chartered.

Whether the Senate Banking subcommittee hearing provoked this or whether this is a desperate attempt by the regulators to reaffirm their commitment towards cracking down on money laundering, what does this really mean for banks and the consulting firms?

The one-year ban on consulting for state-chartered banks applies to the smallest of Deloitte’s four units, Deloitte Financial Advisory services. It does not apply to Deloitte Consulting or any other divisions of the auditor. It is also possible for Deloitte to terminate the ban earlier if it puts in place the state’s new rules for financial consultants.

The crackdown by the New York state department will probably not be lethal for Deloitte but it will cast a dark shadow on its fintech consulting business. The ban might be limited in scope, nevertheless it harms the reputation of Deloitte, and is likely to provoke the banking community to take more responsibility in choosing its consultants and red flags the consultancies who are rather liberal in their reporting practices.

Deloitte was involved in committing fraud, damaging the security of the banking system and affecting national security according to New York State. These, by any accord, are not small consequences of an allegedly cavalier attitude and will have a spillover effect on industry-wide reputational risk. Regional and community banks will surely consider the settlements before signing new contracts with Deloitte, vendor management will be scrutinized and new business will be hard to come by for Deloitte. The number of banks directly barred from using Deloitte’s consulting service are significant: they include some of the largest – Goldman Sachs and Bank of New York Mellon, in addition to more than 4,000 other financial institutions including credit unions and insurance companies and New York units of foreign banks.

Taking the cue from Deloitte’s case, the DFS now proposes an explicit code of conduct for consultants to ensure their independence and make it easier to monitor them. This includes absolute disclosure around the financial work they’ve done and to be in a position to certify the final report to regulators as their own work, in addition to maintaining records of all recommendations that don’t get included in the final report and developing policies on complying with confidentiality rules.

The silver lining around this dark cloud of regulation is likely to be a sense of clarity around best practices for consultancies. This would eventually improve the battered reputations of consultancies and give them the credibility they desperately need. But, it is hard to know whether this will be too late for some: Deloitte could be a harbinger to other consultancies being sent for some quality time in Siberia.

This is also just the start of DFC superintendent, Benjamin Lawsky’s crackdown on big banks that now need to take compliance far more seriously than they have been. This could prove disruptive for banks if other states follow New York and choose to issue their own set of regulations. Banks would need to put together contingency plans to prepare themselves for such a crackdown on consultancies.

Another aspect worth the notice is how many top banking regulators have crossed the bridge to sit on the other side of the grass. Ex-banking regulators now run a shadow network between banks and regulators, a kind of ex-regulator omnibus, that at times even substitutes the financial industry supervisors. They assume themselves to be auxiliary, private sector regulators, and blur the line between consultants and regulators, creating a conflict of interest.

The community that forms this shadow network includes former senior officials from the OCC, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Treasury Department, the Federal Reserve System, the Securities and Exchange Commission and foreign regulatory bodies. This “revolving door” could be blamed for the unhealthy relationship between the government and the private sector.

Some however, argue that such private sector regulators serve the broader public interest by producing manageable regulation and spirit-of-the-law compliance. Given that a number of banks frequently get themselves into woes with their regulators and don’t have the internal expertise to fight their case, private regulators are not likely to go out of business anytime soon.

—

CFPB cracks down on overdraft fees

Around 11:45 pm, on a Friday night in 2011, Jay Leno gave me a fit of giggles as he mocked Bank of America’s plans to charge consumers a monthly debit card fee of $5, in his classic late night television series, ‘The Tonight Show’.

The episode remained etched in my memory for it is seldom that the banking industry becomes the subject of satire in a late night television show.

The report released on June 11th, Tuesday by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) reaffirmed the satire. The regulatory body is gearing up again to criticize the US banking industry for charging overdraft fees that generated close to $32 billion in revenue, in the US alone.

The rigmarole around overdraft fees is not new. It repeats itself every year, and every once in a while the regulators decide they must pull up their socks and attack the banking industry in the interest of the public. Fair enough and good cause, perhaps, if one could be sure that these efforts would lead to constructive outcomes.

The Dodd Frank financial overhaul law in 2010 created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to act as an advocate of consumer interests. Back then, the Fed required banks to give consumers the right to opt-in to overdraft protection for debit card purchases. This came to be called Regulation E. At the same time, the Credit Card Accountability, Responsibility and Disclosure Act required that consumers opt-in to the services. Nevertheless, by the end of 2011, 16% of all consumers had enrolled in overdraft protection plans, and 22% of new account holders opted-in to the plans. That was a surprise to those who thought consumers wouldn’t want to opt in.

Despite the relatively low opt-in rates, overdraft and non sufficient fund fees, these fees made up 61% of banks’ total consumer deposit service charges in 2011.

While one could certainly question some of the practices the banks take with overdraft charges, the banking industry is struggling to turn around its P&L accounts amid the recovery from the 2009 financial crisis. In the absence of this revenue source, $32 billion as I said, banks will be compelled to take to other measures for increasing their revenue which may result in higher annual fees. In the absence of overdraft fees, consumers might have to pay fees for returned checks, late fees and it could eventually affect their credit reports.

And these fees aren’t all bad. The overdraft service acts as a short-term loan for consumers and is a convenient way to raise cash quickly. According to Richard Hunt, President and Chief Executive of the Consumer Bankers Association, “New rules by CFPB could push some consumers to use unregulated industries with riskier and costlier alternatives such as payday lenders, check cashers or pawn shops”.

The probe into overdraft fees could prove costly for small banks in particular, that consider this an important source of revenue growth. Over the years, charges have seen a shift with 12% of banks charging less than $20 per overdraft. This is up from 7.4% in 2008 and 1.3% from 2011. Bank of America and Wells Fargo are the exception in this case and charge $35 for every over drawn item.

Richard Cordray, CFPB’s Director, clarified in a conference call that the agency is not out to ban the product entirely, but to deal with numerous concerns with industry practices. “What is marketed as overdraft protection can in some instances, put consumers at greater risk of harm”, he said.

An aspect that has attracted private class action litigation and regulatory actions, also raised by CFPB, is the question of when charges are posted to the accounts. Some banks post ATM, debit and check transactions in the order they happen and some put them at the top of a day’s transactions that allows them to subject more transactions to overdraft fees.

In its report, CFPB continues to argue for daily caps on the number of transactions that become eligible for overdraft protection and hopes to bring uniformity to overdraft protections. However, similar attempts like the review of overdraft practices in February 2012 and the introduction of legislation in May 2012 have only rubbed the surface of overdraft fees without outlining uniform ground rules for the banks to follow.

Overdraft fees, given their nature and impact, will always invite the ire of consumers and regulators alike but with a slow recovery and low interest rates, what is the alternative source of revenue generation for banks? Cracking down on banks for overdraft fees is justifiable provided the alternative path is clearly defined and really makes consumers better off.